Written by Daniel Park ’21, Mira Pickus ’21, and Raguell Couch ’21

While Durham Academy was officially founded in 1933, as the Calvert Methodist School, the DA Upper School did not exist until 1973. This means the DA high school was established shortly after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and in the midst of national school integration. As students involved with the recent Durham Academy Petition for Racial Equity, we wanted to learn more about the historical narrative of civil action at Durham Academy. What was going on in the 70s at DA? Was the school integrated? How did DA fit into the Durham community at that time? In a way — we wanted to get a sense of what the first generation of Durham Academy activists was like. Here’s a little bit of what we’ve learned.

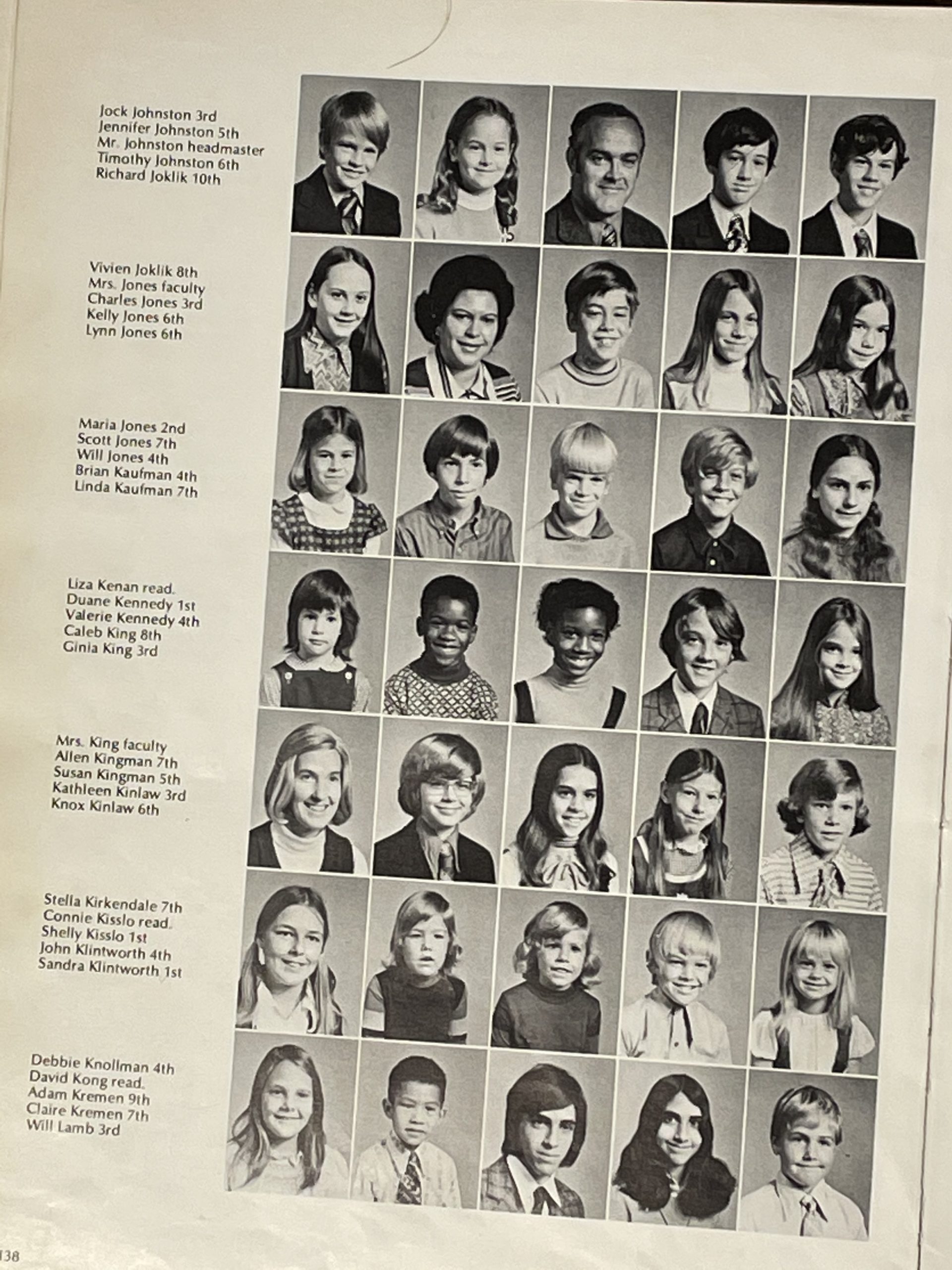

Recently DA Alum Valerie Kennedy ‘81 gave a presentation on what DA was like in the 70s. The first thing she noted was that Durham, at the time, was run by many behind the scenes organizations. She mentioned in particular the “Do Nothing Club” which in fact did a lot. DA’s headmaster was part of this organization (made up of influential leaders from both Durham’s white and Black communities). The club met to discuss Durham race relations. The “Do Nothing Club” was then perhaps particularly representative of the progress being made in terms of integration and racial justice in the 1970s. While Durham had come to a point where powerful citizens of both races could meet and discuss the fate of their city privately, Durham had not yet achieved a level of inclusivity that permitted Durham elites to discuss race publicly. Around the time of the Upper School’s creation, not only was DA integrated, it was also covertly part of plans to continue to better race relations in Durham. 1970s Durham fostered crossovers between the city Black and white elites.

The DA community at the time was hailed from several neighborhoods: Forest Hills, Duke Forest, Fayetteville Street, Emory Woods, and Chapel Hill. Forest Hills was home to the wealthiest and most powerful white families at the time. The owners of the Durham Morning Herald lived in that neighborhood. Duke Forest was, of course, connected tightly with the University. Fayetteville St and Emory Woods were two hubs for Durham’s Black Bourgeoisie — Fayetteville St being closely tight to NCCU and Emory being home to all kinds of black professionals. So students hailed from a mixture of these neighborhoods. They also came from a variety of previous schools. Because the DA upper school was so new — a lot of students joined DA from other institutions like Rogers Herr and other DA public schools. Many of the public schools had already begun two-way integration — busing white kids to historically Black schools, and busing Black kids to historically white schools. Kennedy describes having lots of mutual friends with her DA classmates — people they knew from attending other integrated schools in Durham. Thus paralleling the adult-elite relationships between Black and white Durham-ites, on a student and adolescent level there was also a great deal of interpersonal overlap. But integration both on a city-wide scale and strictly within the DA community, did not come without its tensions and nuances.

The legacy of Black students at Durham Academy is one that continues to find itself at the forefront of many conversations. A particularly impactful piece of history was brought to light when Cecilia Moore ‘22 interviewed former DA students Sally Anita Burnette ’79, Vincent Quiett ’81, Claire Sanders ’79 and Mark Sanders ’81 in “Because of Them, We Are.” While Durham Academy’s complete history is a complicated one particularly with the names it’s connected to, most current Black students are unaware of those who came before them. The former students and graduates’ stories were so rich and complex, they deserve to be a greater part of Durham Academy’s history. Their stories and journeys paved the way for modern students of color in major ways. I initially thought their stories would be marred by racism at school and in the broader Durham community, but many of their stories were intertwined with making friends both Black and white and just being a child, teenager, and student. Many students had attended Durham Academy since Lower School and despite the unfortunate inherent racial tension that occurred, they were still proud Cavaliers. Though much has changed from when they were students, I [Couch] recognized many of my own memories in their descriptions of their years at Durham Academy. Despite our classes, friends, and teachers being unalike, their ever pertinent love for their community and relationships that were born from DA felt deeply personal. It is difficult as a Black person to often be “the first” to achieve something but by honoring them it makes that difficulty a little lighter in recognizing their accomplishments. As a community, we must make a prudent effort to commemorate what seems small, but an ultimately mighty task by these students for helping to create a future that bettered us all.

[The following was written by Daniel Park in investigation of the debate around Kenan auditorium and the history of Durham Academy, with implications for the larger state of North Carolina]

In a normal year, 9th graders at Durham Academy would begin their high school journey as every other class has with commencement speeches held in Kenan Auditorium. Kenan looks a bit oddly situated when compared to the rest of the campus. In contrast to the newly built Krzyzewski family commons, or even the new STEM building, Kenan still bears the wear and tear of decades of use. While other buildings may have transitioned to a more modern red-brick style with state-of-the-art facilities, Kenan Auditorium struggles to keep up, described most aptly by the worn-out carpets and years old gum occasionally found stuck to the bottom of seats. But Kenan still has its charms, students at Durham Academy share countless amazing memories listening to their fellow students give heartfelt speeches, put on amazing shows, and even hear from incredible guest speakers. Oftentimes Kenan auditorium has been the stage for some of the most memorable moments students have had at this school. Throughout the years at Durham Academy, it feels as though nothing has been left unspoken in that auditorium, from the cultural heritage celebrations, student talent shows, to even student-led presentations on entomology, almost everything has been talked about. Except for maybe one thing, the contradictions. Durham Academy makes a lot of effort to appear like an inclusive school. From school brochures to the website Durham Academy seems very diverse. Even a point of pride in the school’s history is the speed at which they were able to open their doors to African Americans in the 70s after the Civil Rights Movement. But for many students, it can feel the opposite, especially when the school doesn’t care to educate them on the school’s history.

Every day, students walk through Durham Academy’s halls, passing by plaques, benches, commemorative photos, and even buildings, carrying the names of prominent families and philanthropists whose imprint is evident even in the larger Durham Area. But not often are those same students asked to question who those people are that were so willing to donate to their education.

Built in the 1970s after an enormously generous donation from Frank Kenan, the school was able to afford an auditorium, a new science building, and also an expansion to their library. Kenan is a very familiar name to those who live around Durham or Chapel Hill. That’s because it’s his family’s name that has been plastered onto the walls of many of the buildings at UNC-Chapel Hill. From the Kenan Flagler Business School, or even the Kenan Memorial Stadium, Frank Kenan’s family’s wealth and generosity has cemented their legacy for generations to come. But as much those who live in Durham and Chapel Hill rely on the legacy that the Kenan family has left behind, much has been left unsaid about the kind of legacy that men like Frank Kenan relied on themselves to get to where they were in life.

To understand the complex and controversial history of the Kenan family and the role they played in the development in North Carolina, we must go back to the 19th century. After the Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved African Americans, the conditions that waited for these people hardly improved. With the introduction of Jim Crow laws and the pervasive nature of racism in the country, African Americans had a difficult time finding success. But that’s not to say it didn’t happen. Despite the many barriers and obstacles in their way, African Americans were able to carve out towns and cities all across America where they built their communities, owning their own businesses and property. One of those such places was Wilmington, North Carolina. Wilmington was a haven for African Americans in North Carolina. It was a booming town, with even its own black owned newspaper. In towns like these, African Americans came from all over, slowly building up wealth and opportunity that they’d never had access to before. But unfortunately, this is the story of how that all got erased.

Success and wealth draws jealousy, and many white supremacists in North Carolina at the time couldn’t stand to see African Americans who were doing better than them financially. In particular, the achievements of African Americans in Wilmington drew the ire of a prominent white supremacist group operating in North Carolina at the time, the Red Shirts. With racist, hateful sentiment still lasting long after the civil war, white supremacists began a propaganda campaign that portrayed African Americans as criminals and threats to white society. By stoking white outrage, the Red Shirts were successful in fomenting a full insurrection and brutally taking over the town of Wilmington. By painting African American men especially as threats to the sanctity of white women, they were able to rally other white supremacists to their cause. On November 10th, 1898, the Red shirts led a mob of white supremacists into Wilmington, killing, burning and destroying whatever they saw. When the fires cleared and the violence ended, estimates find almost 60 African Americans were killed and their businesses destroyed. In particular, the local black owned newspaper, The Daily Record was burned to ashes. This event is special and significant, not only for the atrocities that occurred that day, but because it was the only successful coup d’etat of an American town. Ever. And the consequences? None.

The Red Shirts drove black families out of town, taking over what was left of their businesses and wealth. And over the course of the next century and a half, white supremacist leaders and their remnants would go onto silence and erase that history, keeping this event in obscurity for decades.

But this is where the stories intersect. Of the men who tore through the town of Wilmington, one man’s name is eerily familiar. William Rand Kenan Sr. led a troop of white supremacists through the street, looking for African Americans to shoot. After the event, his family would go on to settle down in Wilmington. Although not too much is known about his life, his son, William Rand Kenan Jr. would later go on to make a fortune, donating massive amounts of money to the University of Chapel Hill. That fortune would end up getting his family’s name immortalized on the Kenan Memorial Stadium, as well as the Kenan Flagler Business institute. A branch of that family, Frank Kenan, would then use some of his fortune to endow Durham Academy with the funds to expand its campus.

So for many students who attend these schools, we’re left in an odd place. In our auditoriums, stadiums, and school buildings, we often hear from teachers and leaders that our job is to make the world a better place. That our job is to make the world more diverse, inclusive, and equitable. Yet it can come to a shock to many of those students that the same buildings that they are sitting in were built with money from families whose ties to white supremacy and racism are deeply entrenched in the history of this state.

As much as it can be hard to say, the Kenan family has benefitted from the massacre that occurred in Wilmington as much as anyone could. But what now? Today we can’t expect the Kenan family to be held responsible for something that occurred more than a century ago, can we? Surely not right? After decades of philanthropy and charitable work by the family, surely there is a statute of limitations on benefitting from acts of white supremacy?

But we can’t begin to hold the Kenan family accountable unless we hold ourselves accountable. As students who’ve sat through spectacular plays, listened to heartwarming speeches, and performed musicals in buildings like Kenan Auditorium, have we, not all benefited from white supremacy? Holding ourselves accountable doesn’t mean that we have to knock down the building. It doesn’t mean grabbing pitchforks and torches either. The first thing we can do is begin a conversation. We can start by brainstorming ways to pay it back to the communities that we’ve indirectly benefited from. The research that we’ve done to find out the experiences and stories of Durham Academy needs to be more available to the students who attend this school. Many students are unaware of our complex history, but echoing the words of Black Lives Matter commitment written by us and our fellow students at Durham Academy, teaching moral, happy, and productive students includes creating informed students, who are connected to the communities that they come from.